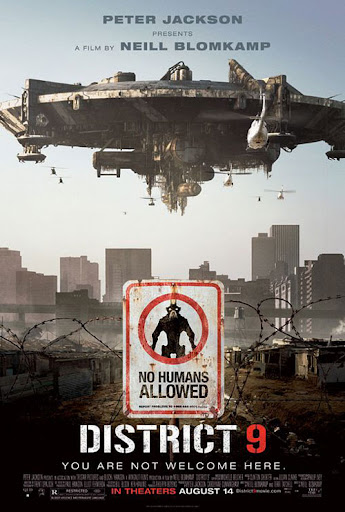

At the surface, District 9 is an action packed, visually stimulating, sci-fi thriller, but in the film, director Neill Blomkamp makes a strong statement on themes of racism and segregation. This movies appeals to various audiences because they can interpret it on the basic level, as an alien fantasy drama movie, or they are free to look at it as a documentary and commentary on apartheid in South Africa, or even more generally, racism and segregation throughout history. The movie’s title is a spinoff on District 6, which is infamous for the forced removal of all non-whites in the 1970s during apartheid command.

The film comes across as extremely realistic, even for a sci-fi movie with such an abundance of CGI (Computer Generated Imagery). Blomkamp’s decision to shoot the movie in Johannesburg, South Africa adds to the realistic feel. Director Neill Blompkamp told wired.com in an interview, “The environment is 110 percent real. It’s pure, pure Johannesburg.” The special effects team does an excellent job of making the aliens seem natural. There are several scenes where the shot is shared between humans and computer generated aliens, but it all looks very real. The aliens are not too flashy, and they seem to fit in well with their environments. The lack of embellishment combined with the camera techniques presents the audience with a realistic setting. For example, there are no zoom shots used in the movie. The human eye cannot see how a zoom shot sees. Therefore, by using camera techniques which the human eye sees daily, the audience is more likely to accept what is on screen as real, rather than stepping back and realizing that they are watching a movie through the collective eye, the camera.

Another unique characteristic of this film is that it is told using a combination of documentary footage, recovered government footage, and news broadcasts. None of these media are specifically elegant or embellished, further giving the viewer a very real feel. If certain shots were too contrived, the viewer would be able to step back and see that he or she is watching a movie; however, by keeping the footage earthy, the audience sees images that they are used to seeing. Seeing a news broadcast is an everyday occurrence to most viewers, so when those viewers see the news broadcasts in District 9, they are likely to accept the news broadcast as true.

The film begins while Wikus van def Merwe (Sharlto Copley) is in his office at MNU, Multinational United. Wikus is a likeable, hardworking field operative placed in charge of relocating the aliens. This is an extremely difficult job because the aliens do not react favorably to being evicted without a say. Quickly, this situation escalates into a battle of humans against aliens. Wikus’ role is fairly clear until he becomes infected while confiscating a canister of some alien fluid. When he realizes that his left arm transforms into a claw, he seeks medical attention and realizes that soon he will completely transform into an alien. Wikus delivers a great, compelling performance and makes it very easy for the audience to identify with him. When Wikus begins to transform, he begins to see the situation from the aliens’ perspective, thus allowing the audience to relate to the aliens.

Although the aliens live like savages and commit crimes, Blomkamp succeeds in forcing the audience to sympathize with them. Although the aliens look like giant insects, Blomkamp gives the aliens with very big eyes. Other films starring wide-eyed aliens include Steven Spielberg’s E.T. and Pixar’s Wall-E. E.T. and Wall-E both feature aliens as the protagonists. The audience relates to these aliens and roots for them because they show emotions like humans do. Even though the aliens are not the protagonists in District 9 (Wikus definitely fills the role of protagonist), the audience easily connects with the aliens. This is in contrast to Michael Bay’s Transformers in which the aliens have tiny eyes. In Transformers, the aliens are extremely flashy, and lack emotional depth, thus removing the realistic feel and discouraging the audience from feeling affection for the aliens. In District 9, the aliens’ large human-like eyes help the audience to humanize the aliens and see the situation from their point of view. Another technique Blomkamp implements which allows the audience to empathize with the aliens is that humans call them “prawns.” Through history, various derogatory terms have been coined aimed at most discriminated groups and ethnicities. The constant use of the word “prawns” forces the audience to view the aliens as mistreated, poor humans, rather than the savage aliens that they are. Another way Blomkamp makes the audience identify with the aliens is by giving them human names and children. After Wikus is infected, he hides with an alien named Christopher Johnson and Christopher’s son. By giving the aliens names, children and families, Blomkamp is humanizing the aliens and thus, the audience easily empathizes with them.

Though Blomkamp ensures that the audience pities the aliens, there are a few questions left unanswered. Whereas most alien films, including The Day the Earth Stood Still and War of the Worlds, focus on first contact between the aliens and humans, District 9 picks up twenty years into the aliens’ occupancy on Earth. The audience never is explicitly told what brought the aliens to Earth in the first place, though it is implied that their ship ran out of gas or broke down above the planet. Blomkamp does not focus on first contact because the discrimination and segregation developed over time. By concentrating on the discrimination, the film effectively serves as an allegory to apartheid.

Another pending question is, why did the aliens choose Johannesburg? As stated above, the audience can guess that the aliens’ ship broke down or ran out of fuel above Johannesburg, but Blomkamp’s motivation is clear. Blomkamp chose to shoot the movie in Johannesburg to make clear the direct connections to apartheid.

District 9 does what very few movies do. It combines visually stunning effects with very powerful underlying themes and it does so extremely successfully while giving the film an especially realistic feel. This combination gives it appeal to a very wide audience and makes it worth seeing.